from EG, The Age (Melbourne), 14 March 2003

Stephen Cummings found New Wave fame, then adult oriented introspection and

is now back to his rockabilly beginnings. Michael Dwyer speaks with him

about music and writing.

Stephen Cummings found New Wave fame, then adult oriented introspection and

is now back to his rockabilly beginnings. Michael Dwyer speaks with him

about music and writing.

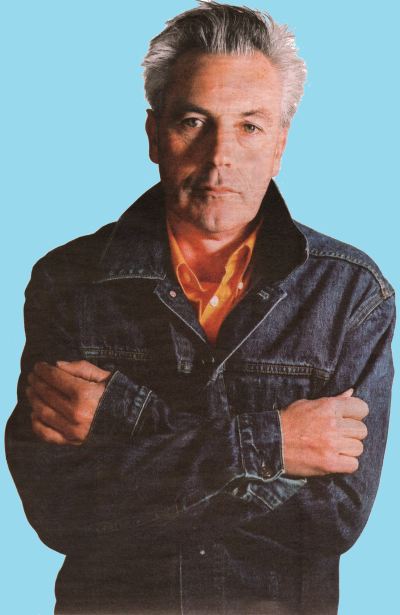

The Brunswick Street busker doesn't realise it, but he's about to become a character in Stephen Cummings' life. The silver-haired singer and novelist in the cafe corner has barely uttered the name Elvis Presley when the guy with the guitar starts yelping a karaoke version of I Can't Help Falling In Love.

Coincidence? Cummings stops, glances sideways, then soldiers on about the King's funky Stax studio mixing desk bootlegs for a slightly comical minute - until the Las Vegas melodrama makes the conversation untenable. "This busker guy," he cackles up his sleeve, "is making a mockery of my words."

Somehow, it's a very Stephen Cummings moment. He's been strangely

uncomfortable in his environment for 25 years now, since his rockabilly

flavoured debut with the Sports, Reckless, mysteriously managed to land that

band in the front line of Australia's new wave boom of 1978.

Somehow, it's a very Stephen Cummings moment. He's been strangely

uncomfortable in his environment for 25 years now, since his rockabilly

flavoured debut with the Sports, Reckless, mysteriously managed to land that

band in the front line of Australia's new wave boom of 1978.

The road he's travelled since has encompassed brilliant radio pop, smoky r'n'b and a dozen albums as a rainy-day singer-songwriter, inspired as much by crime fiction and film noir as Bob Dylan and Bryan Ferry. His upbeat new one, Firecracker, completes the musical circle. Hence the timely invocation of Elvis."

I just got interested in listening to that old rock'n'roll stuff," he explains. "I was a bit bored and thought I'd do a rocking record, a bit of a happier record. I always say, 'This is my last one, I won't make any records after this', so I thought, 'Hey, this'll be good, I'll go out like I went in'."

It may be the detached perspective of a novelist that makes Cummings chuckle at his own dialogue so often, and it may simply be his renowned self-effacing character. Stories of his extreme bashfulness abound, from Molly Meldrum physically restraining him for a Countdown interview circa '79 to his hiding behind dressing-room doors to elude backstage visitors as recently as '95.

At one stage, Cummings has confessed, the Sports broke up for two weeks and then reformed with a new drummer, purely because nobody in the band had the people skills to fire their first one.

These days, he says, he's "much more relaxed", although he does relate with horror a "nerve-racking" recent audience with Jason Donovan, whom he was asked to interview for a glossy magazine. In the interest of full disclosure, he also writes occasionally for The Age. Which is a good thing - in another classic Stephen Cummings moment, the glossy magazine folded that very same issue."

"I'm in the process of writing another book," he says, explaining his rockabilly renaissance by circuitous means, "and every chapter is the title of a single that was on (early blues/rock record label) Chess. The main character in the book is limiting everything in his life. He has one look of clothes and he only listens to things on Chess."

"Chess covers everything, really," Cummings says, the line between his own opinion and that of his fictional protagonist slowly blurring. "You could say that you only need to own six books and about 10 records. Couldn't you?"

Um ...

"Every year I used to go to a second-hand shop and sell all my CDs and say, 'Thank God I got those out of my life!'. Then I'd go, 'Oh, I'd really like to hear Blonde On Blonde now', so I'd go down the record store and buy another one. Have you ever done that?" he hoots. "I don't do that any more, because I realised it was stupid."

Cummings' re-acquisition of rockabilly came with obvious passion and respect for the vintage sound quality of the genre.

"I was listening to all these Chess records and wondering, 'Why do these really jump out at me and modern records don't?'. They're not as dynamic any more. I think it's the space. They used to keep all the space and have lots of percussion.

"If you listen to the Rolling Stones' first four or five records, there's heaps of acoustic guitar on them and heaps of percussion. I guess Brian Jones brought all those shakers and things, and in the mix they sound really powerful.

"Modern records are mixed on computers, and a lot of engineers are basically looking at patterns on computer screens, getting nice waves of sounds. They hate edgy and spiky. Spikes are a nightmare in digital recording, but that's kind of what I wanted."

The quest for authenticity brought him to a couple of hot-shot guest guitarists in Daddy Cool legend Ross Hannaford and the Living End's Chris Cheney, who refused payment in favour of Cummings' autograph on a few cherished Sports singles.

"Chris was the first one to come in and do an overdub, and he sort of set the benchmark. He played the solo on Gone Baby Gone and, really, that could be in Guitar magazine. I mean, you could write that out as a perfect illustration of how to play a solo. He did it in one go."

The singer's original plans also involved ace Melbourne lap-steel player Ed Bates, an original member of the Sports, ousted by Martin Armiger when they took a more commercial pop direction with Don't Throw Stones in late '78. But Cummings' long-term guitar-slinger and producer, Shane O'Mara, wasn't about to be upstaged twice.

"All guitar players are very competitive, I've noticed," Cummings says with amusement. "What was so good about the Sports was that they weren't competitive, because they played so differently. Martin liked to play rhythm and Andrew (Pendlebury) played lead. It was the ideal combination. Otherwise, guitar players usually end up hating each other, I've found."

O'Mara's dexterous playing has effectively covered for an entire band for much of Cummings' solo career. For the Firecracker launch this weekend, however, the stalwart duo will be bolstered by the back-slapping sound of two bassists and two drummers, as well as Hannaford on guitar.

Long a wistful, acoustic kind of performer, this is Cummings' first full band outing since an ill-fated Sports reunion at Mushroom Records' 25th anniversary concert at the MCG in 1998."

I didn't really wanna do that," he says, wincing at the memory. "Then, two days before the gig, Martin broke his leg! I sort of did it for the drummer and bass player (Robert Glover and Paul Hitchins), because I'd been so horrible to them when we were in the group together. Well, not as horrible as the guitar players actually."

Given the retrospective tone of the conversation, combined with the vintage feel of Firecracker, it seems appropriate to produce my old vinyl copy of Reckless for comparative purposes. Half a dozen expressions cross Cummings' face before he eventually responds.

"That was in my heart when I lived in a shop above Malvern. I really don't think about it much, although we could probably be selling more records now if we had thought about it more.

"I remember seeing an interview with Howard Devoto when they were re-releasing Magazine's stuff in a kind of reissue package. He was saying that unless you bang on about yourself like that, people don't realise you were good. Sometimes I feel like that about the Sports.

"We actually did a lot of stuff people don't realise. We did tour Europe, we toured America, we did play on some amazing bills. I remember one gig at the New York Palladium that was the Fall, then the Sports, then the Buzzcocks. We did some stuff. But when we stopped, we stopped. The three main members went on to other things and left that behind."

Which was typical of Cummings' attitude from the start. Each new Sports album - and there was one every year in those five-gigs-a-week glory days - basically rendered the old one redundant. In concert, they played their new record and one or two crowd-pleasing hits, if you were lucky.

"Yeah, we were very unpleasing," Cummings agrees. "We just pleased ourselves. I probably could have furthered my career if I wanted to, but I couldn't be f---ed," he says with a sigh. "We were always like that. And the touring made us crazy. It just didn't suit my personality."

In a sense, the intimate, introverted feel of his solo work was a logical reaction to those increasingly unhappy years in the back of a tour bus. As a writer of tightly focused, filmic vignettes, Cummings hit his stride with A New Kind of Blue in 1989, winning an ARIA for best adult contemporary album. It was a category in which he felt at home. Acting his age in song has long been among his strengths.

"That was kind of my mission, yes," he says. "I tried to do it in a way that was adult and contemporary and not pretending I was something else. That's basically what I've tried to do ever since then. Sometimes it's worked, sometimes it hasn't.

"Doing that first record with Steve Kilbey (Falling Swinger) was a big blast for me, but doing the second record with him (Escapist) wasn't quite as good. Probably never should have done that one. It had a really bad cover. My fault. But at the time it seemed funny."

At the time, it was. Instead of Cummings' 1950s movie-star face, Escapist featured a close-up of a sheep. It was all part of an impulse, he said at the time, "to do everything the exact opposite of what I usually do - like George on that episode of Seinfeld".

But that was during his selling-all-his-favourite-records period. Over his past few albums, he's appeared to find a certain contentment in what he's always done - that is, whatever he wants - but lately with a complete absence of concern about commercial viability.

"When I first got into music, as a fan, music was an other," he reflects. "Now it's the centre of the mainstream entertainment business. It used to be a place for outsiders. Now, if you look at someone like Eminem, how long did it take him to go from outside to centre? It was amazingly fast.

"I could probably be living very comfortably if I'd gone to America about 10 years ago and just been a songwriter. That was an option at one stage, but I just really didn't like America. I'm not a good traveller.

"Writing is a good job," Cummings concludes with a shrug. "Instead of stacking supermarket shelves, I do bits of writing."

Lots of bits, actually. While his journalistic forays are sporadic, Cummings' sheer volume of albums challenges the most prolific Australian artists. And that's before you consider his two novels to date, Wonder Boy and Stay Away From Lightning Girl.

"I think this one's gonna be called Kitchen Man," he confides of the work in progress. "It's about a pastry cook. I've had to read a lot of books about cakes. Making cakes. Cooking cakes. The whole thing about cakes. Basically, the idea is that you can't appreciate your own life until you contemplate that you're gonna die. It's a comedy."

Stephen Cummings launches Firecracker at the Palais, Hepburn Springs, tomorrow, and at the Corner Hotel, Richmond, on Sunday