by Toby Creswell

from Juice magazine, September 1997

Cummings can laugh about it now. The joke is that for someone who has such a

reputation for being difficult, intensely shy, and defiantly uncommercial he has

two "best of" collections released this month - the same month

that he delivers his second novel to the publishers. Cummings is the quiet

achiever, the only artist in the country to survive a 25-year career with his

credibility intact.

that he delivers his second novel to the publishers. Cummings is the quiet

achiever, the only artist in the country to survive a 25-year career with his

credibility intact.

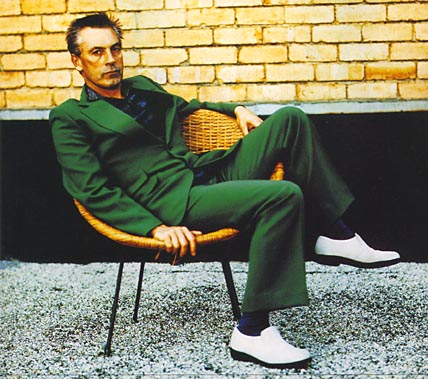

Despite a flirtation with Italian suits in the early 1980s, Cummings has become the Australian worker. Most of his time is spent in his shed, a converted garage in suburban Caulfield that houses his computer, a porta-studio and an extensive record collection of carefully chosen tunes. In the garage, Cummings works on his novels, writes songs and dreams of how to get out of the music business. There's a love/hate relationship with music that drives this cab driver's son.

"I still really love music, I'm still listening to crap," he says, listing Pavement, the Underground Lovers, Bert Jansch and Mazzy Star as his current faves. Cummings is on a post-gig high, having played rhythm guitar the previous evening in a band with Deadstar's Barry Palmer and Professor Chris Marshall. "It's still the main thing that I want to do but I don't want to tour for the sake of it," he continues. "Over the last few years I've enjoyed playing in groups more. I've spent 20 years on my own in a room writing songs. You get too introspective - and I was too introspective to start with."

Stephen once told me a story about his father, who was a cook. In the 1960s he opened the first fish and chip shop in Melbourne to offer beer-battered seafood. This innovation had people coming from all around the city to eat what was regarded as the best fried fish in town. The shop was putting the greasy spoon up the road to shame. Then one day the guy from the milk bar up the road made a disparaging remark about the beer-battered fish and Mr Cummings went into a fit of pique and sold up the shop for fuck-all to the greasy spoon proprietor. He closed down and went back to driving cabs.

Pique runs in the family. Fortunately, however, in show business this is excused as an artistic temperament. For Cummings it has meant that he has tried his hand at many different things without waiting around for the public and success to catch up. He made two of the first independent records of the 1970s, was one of the first Australian songwriters to crack the US Top 40, and made one of the first dance albums in Australia. All this moving around makes it hard for people to categorise Cummings.

"A-grade professional roots music," is how Cummings describes most of the material on his recent albums. "I've gone between pop and dance music and that style, and they're supposed to go together," he explains. "Some of my fans like one thing or the other. I'm not like a Johnny Farnham or a Tex Perkins who concentrates on being a singer of a particular type of song. I don't really want to do that.

"I think the area that I'm covering with these songs is quite unique, and I think I'm getting better at it."

There was a time when Stephen Cummings might have had another career. He was going to be a stand-up comedian and open a magazine in partnership with his friend Johnny Topper. However, Topper was persuaded to spend the money intended to float the magazine on a bass guitar and, with Peter Lillie, they started the Pelaco Brothers. The group created a distinctive style of country and rockabilly with a strong satiric edge and quickly became legendary on the inner-Melbourne scene.

It was a naive time for Australian music and Cummings was still in college. He got his first taste/distaste of touring with this band when they were booked for a six week residency at Gobbles discotheque in Perth, where, according to Topper, "We were totally unsuited. The problem was we weren't paid enough to have any accommodation so we heard of this band called the Last Chance Cafe and we went around to their house and asked if we could stay. We'd never met them before in our lives. I still don't believe we did that. They were incredibly nice about it."

The woman who booked the discotheque took a shine to Cummings. She put the hard word on the singer and was politely rebuffed.

"She said to me, 'Do you realise that for $50 in this town I could have you killed.' I said, 'Yes. But the answer is still no.' We were so broke though we had to go out to dinner with her. I ended up having to crawl out the bathroom window to get away."

The Pelaco Brothers were far too far out to attract the interest of any record companies. They recorded one EP, one of the first independent releases of the era, and then dissolved. By this time Cummings had given up his interest in art school and quickly assembled another group. "I just vaguely met people and dragged them into it," he recalls. "I always wanted Andrew (Pendlebury) in the group as a guitarist and I had an idea for a rockabilly country sound. But I always wanted to change it because I really liked the MC5 and wanted to make it more like that as well."

This wilful eclecticism was a major part of the Sports' sound, and satisfying his broad tastes has been a theme with Cummings for 20 years. Shortly after they started, the Sports cut 500 copies of an EP called Fair Game. A friend in London posted the record to the New Musical Express, which declared it Record of the Week. Suddenly the Sports were elevated from playing the corner pub to contenders, and in the UK the Sports were regarded as an Antipodean Elvis Costello. In fact the group ended up on the same label as Costello, Stiff Records, in the UK.

"We were totally surprised," Cummings says of the NME review. "It was the last thing you'd expect. It was my making and my undoing in some ways. When you have everything go right so quickly you expect that everything after that is going to be good and that easy. It meant that I probably didn't put myself out as much as I should have."

The group signed to Mushroom and a first album, Reckless, was a minor hit followed by the multi-platinum Don't Throw Stones and its classic single, "Who Listens to the Radio." By this time Martin Armiger had joined the group, bringing his more art-rock perspective to the songs. The Sports became a group that could deliver blistering sets of power pop with an intellectual backbone - the closest thing Australia had to a Blondie or Talking Heads.

The band signed to Arista for America and toured behind the hit single "Who Listens to the Radio." The trip got off to a bad start at the showcase gig in New York where, in front of an audience that included Mick Jagger, Iggy Pop and other luminaries, the group fucked up its first song twice. Cummings was so angry he spent the entire show with his back to the audience. The tour was hell.

"A lot of it was me being spoilt and childish," he concedes. "No one told me get fucked - maybe that illustrates the lack of management that we had. But we got tired and run down. We played 300 shows a year for three years and you just get worn out. The thought of touring America and doing it all over again was too much."

By 1981 the Sports had recorded their final album, Sondra (named after Clint Eastwood's girlfriend, Sondra Locke). There were no announcements or farewell tours, just one final EP of mostly obscure Bob Dylan songs. At 27 years of age, Cummings slipped into his quest for something else to do with his life.

He was resolved, however, to stray as little as possible from Melbourne. "I think all towns are the same, but I probably belong in Melbourne," he says. "I can't take too much excitement." Melbourne became the basis for Lovetown, the imaginary city where most of Cummings songs are set.

Unlike their pub rock contemporaries, the Sports had influences from the entire spectrum of pop. One of the most important was Chic, which is the direction Cummings went in next, recording the Senso album for Regular and scoring a hit with the tongue-in-cheek "Gymnasium" and the lush "Stuck on Love". Only two problems - he was totally over touring, and Australia was not yet ready for a dance album. With few other opportunities to promote the music, Cummings had to decide whether to get back into the pubs for 300 gigs a year or scale down his operation.

Unsurprisingly he chose the latter and began recording what he calls "A-grade confessional roots music". Generally choosing semi-acoustic outfits, the albums have highlighted Cummings' distinctive vocal style and his precise, mostly melancholy lyrics. This Wonderful Life, Lovetown, A New Kind of Blue, Good Humour, Unguided Tour, Falling Swinger and Escapist have developed a world of quirky characters, of emotions not quite resolved and pop culture references springing up without warning. Lovetown in 1988 was both the cheapest record he'd made and a breakthrough in terms of emotional directness, though by this time Cummings had largely turned his back on the music industry.

"I have to work within the budget I've got, so I tend to write a certain kind of song," he says. "You could regard that as being shallow or being practical. Of course I want people to listen to my music. Of course I get disappointed that my discs don't sell as well as Hanson. I realise that my music is not quite disposable and instantaneous enough, it requires the listener to venture part of the way."

A New Kind of Blue brought him grudgingly back into the industry and scored an ARIA Award, while its successor brought Cummings back to dance music with the minor hits "Hell" and Sly Stone's "Family Affair".

For the past 15 years, however, the singer-songwriter has been uncomfortable with his pigeonhole. He's dabbled in film - writing, and acting in low budget features. He's written songs for and toured with a ballet company, and written jingles while dabbling in record production. His last job as a producer was working with Melissa Tkautz, whom he describes as the ideal talent because she spent most of the day shopping and only came into the studio to quickly cut vocal tracks.

Then, about four years ago, Cummings began playing with the idea of writing a self-help book for modern parents based on his experience raising his son Curtis. One thing led to another and the book turned into a novel, Wonderboy. Part magic realist fantasy, part travelogue, part self-help book, the story is now in its second print run.

The literary life has kick-started Cummings' interest in music again. As well as making his own albums he wrote and recorded the 4 Hours Sleep project with bassist Bill McDonald and a variety of vocalists, including Angie Hart, David McComb and Edwyn Collins. The last two solo albums, Falling Swinger and Escapist, have been recorded with Steve Kilbey of the Church, who has helped to change Cummings' style yet again.

For the past decade, Stephen Cummings has earned enormous praise from his peers and little in the way of record sales; critical praise does not translate into platinum discs. He has also discovered some great talent - from I'm Talking, featuring a very young Kate Ceberano, to Shane O'Mara and Rebecca Barnard of Rebecca's Empire, who backed Stephen for seven years, to his sidemen, almost all of whom have been poached by Paul Kelly. Perhaps he has missed his calling as an A&R man.

With such a body of work, it was time for a retrospective. Poet, Pauper, Pirate, Pawn and a King takes its name from a Sinatra song and demonstrates how Cummings did it his way as a solo artist. There are also three new songs which fall into the "psychedelic blue-eyed soul" bag - "Slowly Going to Pieces", "Somewhere" and a cover of Flash & the Pan's "Waiting for a Train." Then there's The Sports collection with its quirky Big Star pop and Yardbirds rave-ups, including a dozen previously unreleased tracks. He is even open to the possibility of a Sports reunion gig for Mushroom Records' silver anniversary. Finally he has also finished his second novel, Stay Away From Lightning's Girl, a satiric journey through the music business.

The only downside is that the perpetual question returns - what to do next?

"I'd like to make one more confessional album and call it Spiritual Bum," he says. "Or maybe I should just make a record with Ross Fraser with me singing other people's songs, a different kind of record that would appeal to everybody. I think I am a good singer."